Every spring, as the weather warms up, we want to shed our winter coats and get out with the dogs onto trails and into open spaces. Unfortunately, as our pooches explore the environment with their noses, they may encounter snakes coming out of brumation.

This can cause concerns for dog owners. Many will ask their vets, “What can I do?” Unfortunately, some vets will recommend the rattlesnake vaccine. Touted to “buy time” getting to an emergency clinic or even to ward off the envenomation, the rattlesnake vaccine is an often used but poorly supported treatment for dogs.

The rattlesnake vaccine uses inactivated western diamondback rattlesnake (Crotalus atrox) venom. The manufacturers claim it “is intended to help create an immunity to protect your dog against the effects of western diamondback rattlesnake venom.” However, there is no evidence to support the vaccine being effective, and some data suggest it could be harmful by causing an allergic reaction to snake venom.

The American Animal Hospital Association (AAHA) recently released a statement highlighting the lack of evidence of vaccine (toxoid) efficacy. Read It Here.

Key points from the AAHA’s statement:

1. There is NO published data supporting the efficacy of the vaccine in dogs.

2. In a study that was performed in mice, where mice were given 50-1,500 TIMES the dose of the toxoid given to dogs during routine vaccination, survival following exposure to snake venom was still not guaranteed, and some vaccinated mice actually died or required euthanasia earlier than unvaccinated mice exposed to the same amount of venom.

3. Adverse reactions, including anaphylaxis, have been reported in vaccinated dogs.

4. Though the manufacturers make claims of cross-protection (protection from envenomation by pit viper species other than the western diamondback rattlesnake, the species used in the production of the toxoid), there are no data to support this claim.

From the AAHA: “Veterinarians choosing to use this toxoid should be aware of the lack of peer-reviewed published data. Polyvalent antivenin therapy is an alternative to vaccination in suspect cases of rattlesnake bite.”

The vaccine did not prove effective in a retrospective study looking at 272 cases of rattlesnake envenomations in dogs. Read It Here.

Key findings from the study:

1. There was no evidence that vaccination lessened morbidity or mortality.

2. No measurable benefit could be identified associated with rattlesnake vaccination.

From this case series: “Vaccination for protection of the general canine population from rattlesnake envenomation cannot be recommended by these authors.”

Furthermore, the rattlesnake vaccine toxoid may predispose snakebitten dogs to anaphylaxis by providing the necessary sensitizing exposure to snake venom antigens. Read It Here.

Key findings from the study:

1. There are no peer-reviewed publications providing evidence of clinical efficacy in snakebitten dogs.

2. Anaphylaxis requires prior sensitization to an antigen; it is proposed that repeated vaccinations with the rattlesnake toxoid vaccine serve as a sensitization event to snake venom.

From the authors: “These dogs had previously been vaccinated with the C. atrox toxoid vaccine on more than one occasion, which may have served as the initial sensitization required for the development of anaphylaxis.”

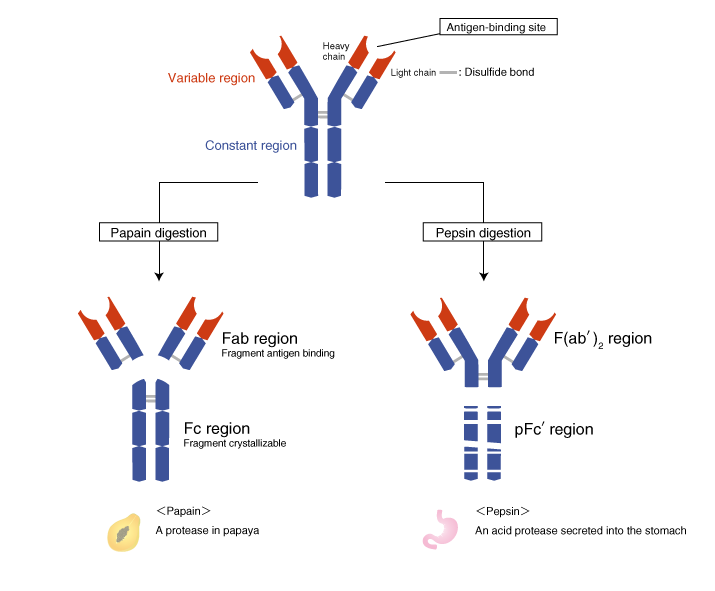

Snakebites are medical emergencies for pets and humans alike. Effective antivenom is the only thing that can neutralize venom and improve outcomes.

If you would like to learn more about veterinary ativenoms, please see this post by Dr. Cory Woliver (A Primer on Antivenoms Used by Veterinarians).

If you found this article helpful, please consider donating to ASF today. Every donation is 100% tax deductible and goes directly to patient care in Africa.